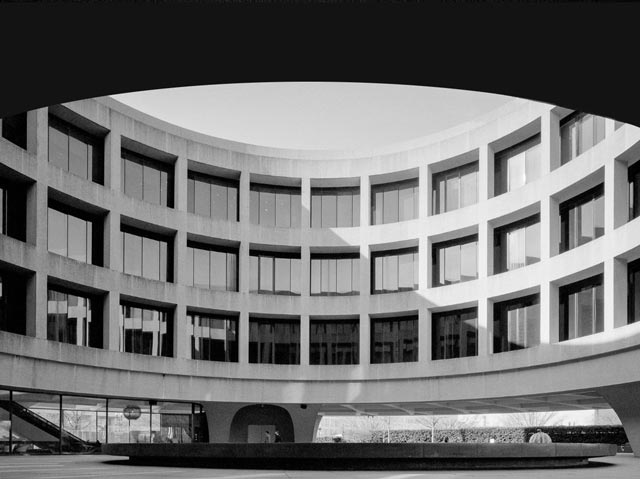

It was the Fall of 2012 and I had already tasted the valuable experience of working for think tanks and intergovernmental organizations in Washington, DC. I longed, however, to obtain first-hand experience in the capital’s arts and culture scene. Having expressed this pressing desire to Spain’s Cultural Attaché in the United States – he had been one of my former bosses shortly after my graduation from Georgetown University – he generously reached out to the Curator of Contemporary Art at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Adam Budak. I met with him and he enthusiastically invited me to join his team as his intern. I could not feel more delighted. I recall his praise for my knowledge of foreign languages as well as my training in diplomacy. “Those are skills that will serve you well as a curator,” Budak said.

At that time, Budak was developing the upcoming exhibition (six) conversation pieces: Republic of Letters. He envisioned this exhibition as the first of a series that would eventually show other kinds of republics. At this occasion in particular, Budak wanted to show works by artists with close ties to the realm of the written word. I recall him gleaming over the work by Rémy Zaugg, for example, whose straightforward messages in bold fonts and colors took over the canvas to create rather exciting combinations. For this exhibition, Budak also intended to invite performing artists who would recite famous works of literature. During this selection process, he did not discard new possibilities and it therefore became clear to me that his ambitions were large, along with his commitment to bring international contemporary art at the forefront of the institution he served as curator.

Budak was passionate about painting, sculpture and installation. I helped him to produce background information on artists that he considered including in the show, and I conducted this research both online and browsing through the several art history publications in the Hirshhorn’s on-site library. Moreover, Budak opened my eyes into the usage of art museum terminology to draft correspondence and execute multilingual translations of email communications between him and other various pertinent publics, including the artists themselves. Budak also guided me into becoming familiar with museum collection documentation. I will never forget the light of his smile when, quite spontaneously, he asked me to follow him to the Hirshhorn’s storage room. Budak summoned me to assist him with unwrapping a carefully packed canvas that was inconspicuously laying on a large wooden table. Seconds before completing our task in unison, Budak gasped: “it is a Sonia Delaunay!” I can still recall the vivid, intricate colors of this artist at the time unknown to me. Years have passed and I still regret having misplaced the name of the artwork that I had the privilege of admiring up close. Years have passed and, every time I see another artwork or reproduction of Sonia Delaunay, I still cling to the hope that my mind will activate this memory so that I may finally recognize that formidable oeuvre I saw with Budak.

I am certain that more moments of discovery would have followed the course of my internship with Adam Budak. An unfortunate event, however – and which I can only understand as a professional misunderstanding – brought my internship to a standstill: the firing of Budak from the Hirshhorn Museum. It was a cloudy afternoon when I received this news directly from him. With tears in his eyes, he gathered the strength to look into mine and say that if I wanted to continue learning about curatorial work, he could recommend me to a colleague of his at the Phillips Collection. I nodded and thanked him for the possibility to embark on another chapter. And while (six) conversation pieces: Republic of Letters never saw the light, I will always treasure its metaphysical existence as my first training ground.